For more professional updates, see our Quarterly Lab Update, which we published yesterday.

Long-termism is the excessive prioritization of the long-term over the short term.

What is wrong with long-term thinking?

Long term thinking is a good thing, right? How can one be against planning for the long-term?

I am not against all long-term thinking, but I am against the idea that “long-term is always better.” I think that there are several problems (all related, but not identical) and that our politics and institutions are now too long-termist.

The knowledge problem of long-termism. This is the fundamental problem: the further ahead in time we look, the less we know about how things will play out. You may be planning for a world that simply will never come to be.

You might spend decades planning a space mission based on the assumption that getting things into space is very ridiculously expensive and then Starship comes along and makes it 1000x cheaper so your whole program suddenly stops making sense. Entire careers can be spent planning and building things that are simply never going to be useful.

The lack of feedback problem of long-termism. It is not just that the rest of the world changes. Often we don’t know where we are going until we get there. In software design, the classical 1950s view (which was always a strawman idea, but did also capture something real) was the waterfall method: first you design the architecture, then you implement, then you deploy. We have since realized that great things are done through iteration.1

And while purely technical artifacts can be planned, any time systems are going to interact with humans, with culture, with lifestyles, there is an element of chaos and unpredictability. You don’t know how things will work until they exist. If you don’t allow for iteration, you are effectively insisting on a one-shot approach: either things work out the first time or they don’t.

The incentive problem of long-termism. While the control problem applies even if everyone is really trying their very best, with long-term feedback loops, incentive problems become endemic. If I am being evaluated in the outcomes of my projects and results are apparent quickly, then I will be incentivized to produce good results. If, however, the results are only apparent with long delays, things change.

A particular regime shift happens once delays are so large so that one is evaluated before the success of failure of the project can be evaluated.

Near where I sit now, there are plans to build a school. There have been plans to build a school for years and the school is unlikely to be finished for several years. Not a single individual with power to influence the building of this school will have been in the same position from the start to the end of the project. There will no one about whom you can say “that person did a good (or a bad) job with this school project.” There will have been multiple election cycles, the bureaucrats at the top of the agencies responsible will have been promoted/retired/moved on… There is no single person to praise or blame.

This dilution of responsibility across time means that not a single individual has the right incentives. In fact, once the regime shifts towards, while actual completion of a project does bring benefits (who ever happens to be mayor or education minister when the school is opened will be certain to take credit); it also brings risks (what if the project is not actually good?).

Public goods are good

One very common mistake is to confuse the concept of long-/short-term with that of public goods. A public good is something that is for everyone.

For example, I think basic science is a public good and should get public funding. Scientific knowledge is an example of a a public goods that does generate value over the long-term because it is a capital good (like building a highway generates value over the long-term), but others don’t (removing ice from the roads is a public good with immediate benefits for the public).

This may seem like a nitpick, except that long-termism often stands in the way of public good provision. Removing CO₂ from the air is one of the purest examples of a public good and long-termism is standing in the way of achieving this goal.

On the other hand, the purest public good in the world, Wikipedia, is based on one of the short-termiest approach for how to build a knowledge base: just make it publicly editable and fix the problems that arise later.2

Long-termism is destroying the climate

Germany just unveiled a plan to become climate neutral by 2050, China aims for the same by 2060, the EU’s Green New Deal is similarly aiming for 2050. Some of these plans, like the US’s, include intermediate milestones for 2030, but none of them fit into one or two election cycles. This means that none of the people signing these pledges now will ever be held accountable for failing to meet them (or celebrated for meeting them)—everyone will be out of power and/or dead.3

Lest you think that it would be physically impossible to achieve meaningful progress in the short term, France decarbonized its energy production in <10 years:

Merkel was German Chancellor for 16 years. If she (and the German electorate) cared about climate change, she could have led the German government while it built nuclear power stations, and almost eliminated emissions from energy production.4 Combined with electrification of transportation and heating, she would have had enough time in power to have been the “Chancellor that solved climate change.”5

But long-termist thinking says that “nuclear is not the future,” so we cannot solve climate change with nuclear power6 because it may be the case than in 20 years, we will want to switch to hydrogen generated by wind or nuclear fusion or that battery technology will have finally scaled up to the level that is necessary to solve the problem of unreliable wind energy. So, we stick with burning fossil fuels and keep emitting CO₂ while pure-renewable approaches are always 20 years in the future.

A short-termist would say “well, we build 30 or so nuclear power stations now and, if in 2035, Elon Musk has solved nuclear fusion, or wind-power-generated hydrogen finally makes sense, we can always switch to it later.”7

I picked on Germany and Merkel because she was in power an extraordinary amount of time (16 years), but this is still barely half of the 30 to 40 year timeline that most climate pledges aim at. Leaders who are in power for 4 or 8 years (the typical in developed countries) have almost no incentive to follow-through with any of these pledges. Even non-elected leaders8 rarely have such a long tenure.

What about short-termism?

How can you deny that short termism is a problem? This post is not to deny the risk of short-termism. There is plenty of short-termism, but there is also plenty of anti-short-termist texts out there. If you Google “the problem with short term thinking”, you will get many hits about the problems with short term thinking. However, if you google “the problem with long term thinking”, most of the hits (almost all of them) are also about the problems of short term thinking.9

If you work in software, you will have seen what happens when a system is under-engineered and just a jumble of spaghetti code. However, you will likely also have seen what happens when a system is over-engineered. You will have seen systems that were delayed (or never finished) because they were made so general, planned for so many future expansions, that they never properly addressed the motivating problem. In physical infrastructure, we have seen short-termism lead to lack of infrastructure and long-termism lead to expensive infrastructure that never gets used.

There is a balance to be found and it is often a dynamic one, whereby systems are always verging between too long-termist and too short-termist (including both at once, when considering different aspects and angles). Constant course correction is needed.

In software, excessive long-termism prompted the rise of Agile. Right now, it’s likely that we are in other phase of the cycle and too short-termist; we need a bit more long-termism in software.

However, in the political world, and in climate policy in particular, we need some short-termists! And we need them fast.

Related links

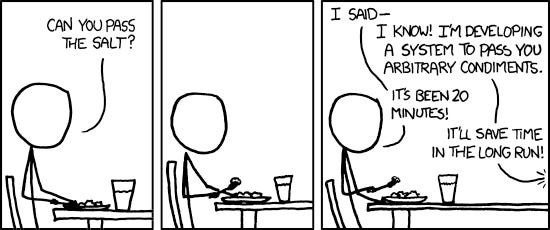

The classical anti-longermism xkcd:

A similar take on long-termism (and more) on Matt Yglesias’ Slow Boring

A related concept is Make to Know, featured in a recent econtalk episode.

Over time, it has become less short-termist, but only after the actual encyclopedia was already one of the greatest achievements of humankind.

“In the long run we are all dead” — John Maynard Keynes

Also, this would have left Germany on without its current dependency on Russia.

She did preside over a reduction in emissions, but many European countries reduced their emissions and Germany is still one of the worse when it comes to CO₂ emissions.

Don’t get me started on the trend to call solving problems “solutionism”, which is a level of stupid that requires a PhD.

What about the cost of nuclear power? We pay it because that’s what reasonable societies do when they are faced with huge problems like climate change.

We are paying already in all sorts of weird cost increases here and there, including random strange stuff like being forced to install an expensive heat exchange system that makes a lot of noise and does not even work, so that I open the windows in the Winter while forcing the CO₂-emitting heater to work double shift. I frankly doubt that the lifetime increase in my electrical bills that would results from a wholesale switch from fossil fuels to nuclear would ever be as much as money as we paid for this non-nonsensical regulation-mandated “ventilation system” (also electric heating would not generate this enormous amount of acoustic pollution).

Non-elected leaders are abundant in democracies, mind you. In fact, important institutions such as regulatory bodies, the courts, and others are often explicitly shielded from electoral interference.

As the kids would say, there is no alpha left in anti-short-termism.